July 26, 2017

District Days Series: Blame Congress? Try Reaching Out First

Posted by cbunge

This Bridge post is a part of AGU’s District Days Series. Throughout August, Members of Congress will be back in their home states and districts meeting with constituents. As a part of August recess, The Bridge will highlight voices of AGU members that have been engaged with their legislators both in DC and back at home. Check back with us next Wednesday to hear more stories of AGU members standing up for science! For more information on how to schedule your meeting with your legislator, check out AGU’s District Days website.

Scientists — embrace your constituent power. Constituents have enormous influence when they reach out to their elected officials; contact from researchers is especially critical when Congressional expertise is shrinking due to lower staffing and high turnover.

In June, a Gallup poll found that Americans have more confidence in news on the Internet (16%) than in Congress (12%). On this—if seemingly little else—Democrats and Republicans are in almost complete agreement, with Congressional confidence levels at respectively 14% and 11%. Yet few Americans reach out to their elected officials, even on issues like climate change about which they feel strongly, believing that Congress doesn’t care what they think. Indeed, a lot of academic and media ink has been spilled pointing out that Congress doesn’t listen to Americans, unless they have lobbyists and campaign dollars to burn. But here’s the thing—Congress listens to the people who show up—who email, Facebook, call, and write letters—and who literally take a seat at the table. Constituents have enormous power, but only if they use it.

As climate change is written off the federal agenda, few contact elected officials

In the first six months of the Trump administration, climate change has been removed from public websites and federal policy. In protest, the People’s Climate March on April 29th drew more than 300,000 people to Washington, D.C. and events across the country. Yet a survey fielded just a few weeks later found that few Americans had contacted an elected official in the last year to urge them to take steps to reduce global warming. Currently in press, the Yale and George Mason University study reports that only one in eight registered voters (12%) have contacted an elected official during the past 12 months to urge them to take steps to reduce global warming. Liberal Democrats are the most likely to do so with three in ten (29%) saying they had contacted an elected official. Only 14% of Independents and 13% of moderate/conservative Democrats have also done this, and 4% percent of Republicans.

Constituents are important to Congressional offices

Ironically, while most Americans do not consider contacting their elected officials to be their civic responsibility, Congressional offices—particularly those in-state—believe it is their job to listen and respond to constituents. Congressional offices are organized to do two things: 1) support the legislator in meeting the demands of the job, including providing them with the information they need to make decisions; and 2) provide constituent services. Some members of office staff are more closely focused on supporting the legislator: legislative assistants, communication staff, schedulers, legislative director, and chief of staff. Others have jobs dedicated solely to communicating with constituents and helping them navigate federal programs: assistants who handle office calls, legislative correspondents who respond to constituent letters, outreach staff, and state office case workers who help their state residents navigate federal bureaucracy. But constituent concerns, both those of state residents and other national issue stakeholders of the interest to the office, remain of vital interest to all staff and of course, the legislator.

Congressional staff have increasingly impossible jobs

Visiting Senate and House offices can feel glamorous, especially when you pass through the throngs of media waiting to catch a quote or photo of a Congress member. But the people who support members of Congress—including those who write this nation’s laws—are underpaid and overworked as staff sizes decline, and their Congressional research support organizations similarly shrink. One recent estimate pegs the salary needed to afford a 2-bedroom apartment in Washington, D.C. as more than $100,000. On top of paying rent, Congressional staff are likely to be saddled with paying off student debt from college and graduate school. Yet, in 2015, legislative assistants in the House—the people writing the legislation that Congressional members vote on—made less than $50,000 a year, a decrease of almost 16% over 10 years.

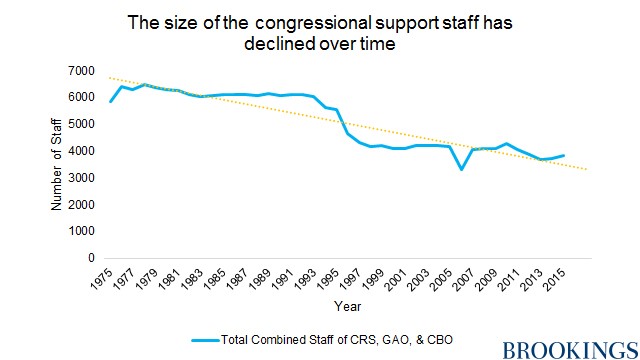

The pay is bad, and the job is getting tougher. By 2015, staffs for members of the House were only three-quarters the size that they had been in 1986, and staffing for the research organizations that work for Congress—Library of Congress, Government Accountability Office, and the Congressional Research Service—was down as well, by more than 40% for GAO alone since 1979. Unsurprisingly, these conditions fuel Congressional staff turnover. The call of earning much more in the private market encourages short stays in Congress, and lowers office levels of policy and issue area expertise.

Visits are the most effective way to build relationships with Congressional staff

With so much turnover, issue expertise is in demand. The people who typically fill the void are lobbyists; the Sunlight Foundation estimated in 2010 that almost twice the amount of House staff salaries was spent on lobbying in D.C. Constituents with issue area expertise can also be a valued resource.

Of the many ways to communicate with your legislator’s office—from letters and calls to social media—visits are one of the most effective. In a 2017 study, the Congressional Management Foundation found that in-person visits have the most influence on policymaker decisions. Over the course of 10 years, three surveys of Congressional staff found that between 94-99% said that “in-person visits from constituents” would have “some” or “a lot” of influence. Visiting with in-state or Washington, DC-based Congressional staff provides the best opportunity to develop relationships with them. According to the same study, 79% of Congressional staff surveyed said the most important way of building relationships was to “meet or get to know the Legislative Assistant with jurisdiction over their issue area” and 62% said “meet or get to know the District/State Director.”

Embrace your constituent power

As Robert Putnam illustrated in his 2000 book, Bowling Alone, Americans have become increasingly less civically and politically active. We a pay a cost for our inattentiveness in the weakening of the social fabric of the communities in which we live, but we also pay a cost to the democratic function of our political bodies, including Congress. Your Congressional offices are set up to listen to you, the constituent. Embrace it!

Karen Akerlof is an AGU Congressional Science Fellow and social scientist who studies the communication of science for policy.

Good column.