January 13, 2014

The Polar Vortex Gets Its 15 Minutes of Fame

Posted by Erik Hankin

Written by Dan Satterfield, author of Dan’s Wild Wild Science Journal.

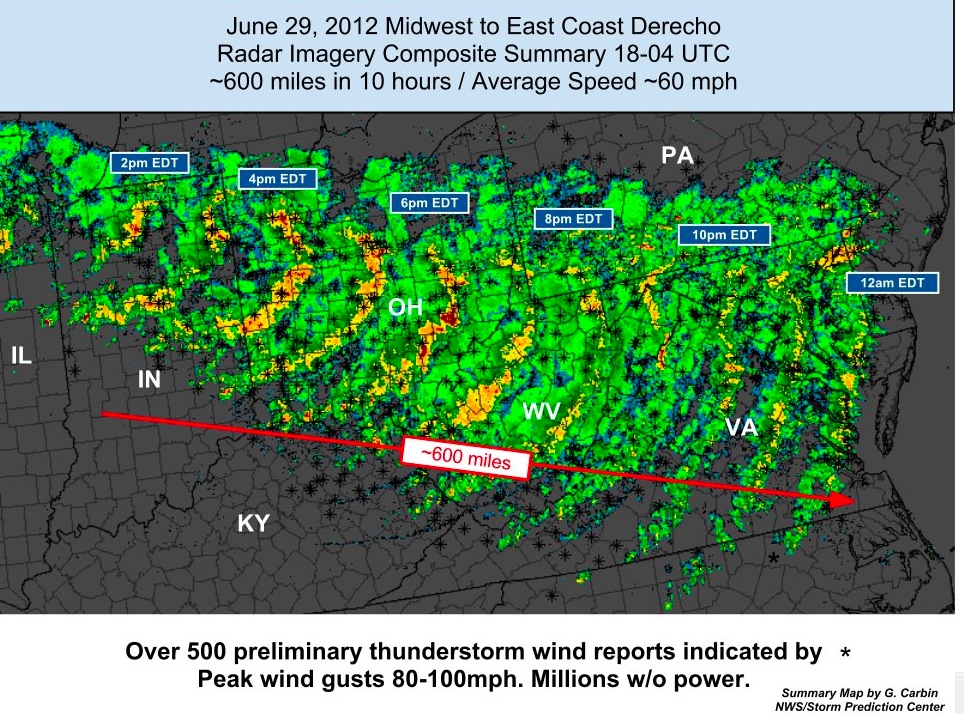

Every science has its own language and terms, and meteorology has more than most. It’s strange though how every now and then, a scientific term you’d only hear if you were listening to a group of meteorologists discuss weather gets turned into a water cooler topic. In 2012, it was the term DERECHO (dah-ray show), when one came through the mid-Atlantic (and knocked down a million trees and power lines from Ohio all the way to the Eastern Shore of Maryland).

Now, the polar vortex has gotten its 15 minutes of fame. The cold outbreak at the beginning of the year was certainly one of the more severe chills in a couple of decades, but by no means as bad as what we saw during several winters in the1970’s and 1980’s. In the past few days I’ve seen images on TV news of snow, frozen lakes, and high winds that were labeled as the polar vortex, but they were wrong. The polar vortex is high above the surface and what you were seeing in those news reports was, (wait for it), snow, frozen lakes, and high winds!

While my fellow meteorologists have cringed as the public tries to make sense of this new word in the public’s weather dictionary, I think it’s a wonderful teaching moment. Albert Einstein said that science should be made as simple as possible, but no more so, and I cannot accurately explain the polar vortex in one sentence (or even one paragraph), but I can do it in three or four. So, if you will bear with me, I promise it will be quite interesting and you’ll never look at a TV weather report the same again!

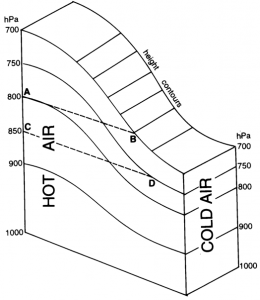

The pressure drops off more slowly as you climb up high in a warm air mass compared to a cold one. This image is from a meteorology course taught by Dr. Bart Geerts at the Univ. of Wyoming.

The polar vortex is a result of the thermal wind, and to understand it we must do a thought experiment. The first thing you must do is to quit thinking of weather as what you feel at the ground,because the atmosphere is three-dimensional!

Over the tropics (where the air is warm) the atmosphere expands just like the air inside a hot air balloon when you heat it up, and over the colder poles the air scrunches down. This leads to a rather amazing effect. Look at the graphic on the right, and imagine that you climbed up a tall ladder from the ground where the pressure is usually around 1000 millibars to point C where the pressure is about 850 millibars. This about 1500 meters up by the way, so it would be a TALL ladder!

Now pretend that a friend is standing at the weather station in the Canadian High Arctic (which is point D on the graphic) and he has a ladder exactly as tall as yours. He climbs up to the same height and measures the pressure with his fancy barometer, and finds it’s only 750 millibars! If you were to both climb higher and higher you would find that through the troposphere the difference in pressure between you and your friend gets larger and larger.

This is because the air pressure drops of much more quickly in the cold atmosphere over the polar regions than in the tropical air down south. Still with me? Good, because you can relax. The rest is straight forward!

You know that air flows from high to low pressure, so a blob of air at point C is going to look at point D and rush northward quickly. The same will happen to air blobs at higher levels, and they will move even more quickly because the pressure difference is even greater! That blob will not get there though, and have you figured out why?

The Coriolis Effect!

The Earth is turning and anything moving over it (from a hit baseball to blobs of air) appear to be turned to the right (in the Northern Hemisphere). Sit on a playground merry-go-round with a beach ball, and you’ll see the Coriolis affect in action!

So, our blob of air rushes north but gets turned to the east, and this is why the winds aloft blow from the west, and it’s also why the winds get stronger as you go higher in the atmosphere (because the pressure difference increases as you climb up that ladder!). Meteorologists call this the thermal wind and the same thing happens if Dallas is 30°C and Omaha is -10°C. The bigger the temperature difference north and south over a small area, the faster the winds aloft will blow, and where the temperature differences are greatest is where the Jet Stream will be. It’s the temperature differences that MAKE the jet stream! Pretty darn cool if you ask me!!!

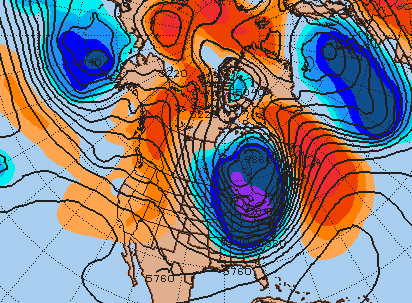

Image from Penn State Univ. Meteorology. This is last week during the polar outbreak over the eastern areas of North America.

When we have a blob of really cold air near the poles, the same thing happens, since we get higher pressure around it and lower pressure underneath it and THIS is called the POLAR VORTEX. The chart on the right shows the pressure pattern about 5km high during the frigid polar outbreak last week. It’s called a 500 millibar chart and shows how high up you have to climb to reach a pressure of 500 millibars. The wind flows with the lines and you can clearly see the polar vortex.

Notice in the second image below, that it has now retreated back north to where it usually is. It’s just as correct to say that the cold air pulled the polar vortex south as it is to say the polar vortex brought the cold air south. The winds aloft move the highs and lows and fronts, and the temperatures at the ground control the winds aloft!

So, now you know what the polar vortex is. Contrary to what a right-wing radio host claimed last week, it wasn’t invented by evil climate change scientists to explain the cold. Believing that all that science is wrong because a small part of the planet gets cold in January does not show poor critical thinking skills, it shows a complete lack of them. The planet is actually very warm right now, and November was the hottest month globally on record. Statements like this actually help more than hurt.

It’s a waste of time to try and convince people who reject well understood science because of a fixed political world view, but it illustrates to those who are more open minded just how far from objective reality some of these statements about science really are.

There IS a real scientific debate right now about whether rising greenhouse gases are causing the polar vortex to behave this way. Dr, Jennifer Francis at Rutgers Univ. has published papers showing an apparent connection, but some other scientists are not so sure. One thing we can say is that when we find the answer, we will have learned something new about how the planet works, and greenhouse gases will still be warming the planet.

I’m sorry that you feel that trying to convince deniers is a complete waste of time, and perhaps it is. My experience with the mentally ill shows that you are right – there’s no convincing them – their circuitry is faulty. However, I refuse to allow these individuals who are being manipulated by others with financial interests to maintain the status quo to control what is being said. Furthermore those same interests make it appear that their numbers are far greater than what they actually are. That’s scary for our democracy.

With the recent projections of a 4C rise by 2050, the stakes are too high to not fight this menace anyway I can. As far as I can tell, this is the final battle and one that can not be lost. Your fight, Dan, needs to come from within and it needs to be radical. Find it, it’s there, and fight like your life depends on it. Because it does.

The article mentions a second image that shows the vortex location back to normal, but the image is missing.

What an excellent post. Thanks Dan

Coriolis EFFECT, not ‘affect’, please.

Back in my day, the “polar vortex” referred to stratospheric easterlies that developed (usually) over Antarctica in the winter, not to traveling cyclones (associated with Rossby waves) in the NH troposphere.

I thought it was still the case, but maybe I am out of touch with the latest terminology trends. There is a “wave” of interest for the polar vortex right now but it is apparently not referring to the stratosphere anymore. Wikipedia also suggests that the cold was triggered by a Stratospheric Sudden Warming event. Although there was an abrupt decrease in stratospheric NAM at the beginning of January, I think it was a bit premature from them to say it is a SSW event…

[…] 2014-01-16, 1140 ET: Two more pieces on this subject, another by Dan Satterfield, specifically requested of him by the AGU, and one by Dr Bob Henson of […]

I would like to say that that I am happy that I now understand how wind patterns spin in opposite directions in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. I had never heard of the Coriolis Effect before this class but it is very intriguing how our planet actually works. This whole Polar Vortex thing sounded like a crock when I first heard of it but not it all makes sense. All the cold air from the north has to go somewhere and unfortunately it decided to land on our doorsteps. I would love to know if anything further is determined regarding the polar vortex and green house gases.

Good post. I learn something new and chalklenging on sites I stumbleupon everyday.

It will always be exciting to read articles from other authors and practice something from other sites.