April 23, 2014

Keep calm, carry on and prepare

Posted by kcompton

Written by John Schelling, Washington State Emergency Management

The invitation to contribute my perspective on tsunami risk reduction efforts to “The Bridge” arrived on my tablet as I sat in the Snohomish County Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Everett, Washington. There I was—working as part of the response and recovery effort to a major landslide (the Oso landslide, which occurred at 10:37 a.m. on March 22)–and presented with the question, “Just how much of a threat are tsunamis, really?”

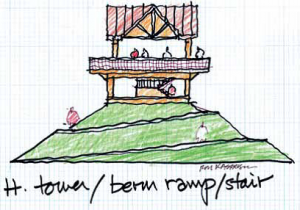

Combination berm-tower structure in profile view

Combination structures offer the advantages of two types of structures: berm and tower. In the berm-tower combination, the footprint in reduced by creating a tower platform that is accessed by a series of ramps and/or sloping berms and can reduce visual impacts of hardened towers or large berms. Credit: Ron Kasprisin, University of Washington

The Oso landslide was a localized event that affected three small communities in the foothills of the Pacific Northwest. However, this disaster features some of the very same challenges and opportunities, to mitigate losses as we see with an earthquake and tsunami.

With the recent earthquakes that rocked Chile and the Solomon Islands in the same timeframe as the Oso landslide and the 10-year anniversary of the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami on the horizon, it’s appropriate to reflect on the past, take stock of our progress, and consider what the future might hold.

The Great Sumatra–Andaman earthquake and tsunami, which claimed more than 230,000 victims on that fateful December day in 2004, was a pronounced tragedy felt throughout the world. In the United States, Congress recognized our shorelines face similar threats; that our tsunami warning system needed to be improved and that our coastal communities needed to be better prepared for the day when an earthquake and tsunami strikes U.S. shores.

In 2006, Congress passed the Tsunami Warning and Education Act (TWEA), which expired in 2012. TWEA helped solidify work that had been underway since 1995 as part of the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program (NTHMP). Through the NTHMP, remarkable progress was made in a relatively short time to improve the readiness of coastal residents and visitors. The message was getting out to people that they had to evacuate at a moment’s notice when the ground begins to shake from a local earthquake, a precursor for a potential local tsunami, and they knew where to go. Despite this substantial progress, more work remains.

Improvements in scientific research of tsunami sources and the technological side of the warning system have enabled states, like Washington, to actually eliminate the need for dangerous evacuations. During the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, we went ‘all in’ on the tsunami warning system and the science behind it. And it paid off, negating the need to evacuate the entire ocean coast of Washington State. It also paid off for Alaska, Oregon, California, and Hawaii when they could respond effectively to a Tsunami Warning issued for their coasts.

The reality is that many of our coastal communities are poised to respond more quickly and are much safer today against tsunami threats than they were in 1995. However, some communities are better prepared for a distant tsunami than for one closer to home. Many coastal areas do not have high ground for evacuating away from a local tsunami. In these cases, using a strategy called vertical evacuation is perhaps the only way to improve life-safety.

Through the NTHMP, Washington State initiated an effort known as Project Safe Haven to empower local communities that lack natural high ground to develop plans for integrating multi-purpose reinforced towers, buildings, and berms into the natural and built environments. And, we’re seeing results. The voters of Westport, Washington recently approved a local bond to construct the nation’s first tsunami vertical evacuation refuge as part of new elementary school. In the coastal community of Long Beach, Washington, the city council approved an application for construction of vertical evacuation berm adjacent to the community’s school and downtown business district. That application is currently in review with the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Following disasters, like the Oso landslide or Great East Japan Earthquake, we talk a lot about ‘lessons learned’. But, we must have the opportunities and resources to apply the solutions once we’ve learned the lesson. One of the key lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake is the need for continuous updates of hazard assessments. Who knew that a subduction zone was capable of 50 meters of slip? Now that we know, we need to revisit previously held assumptions and perhaps revise prior hazard maps, evacuation areas, and evacuation routes. Like preparedness, this process is never done. There has to be a feedback loop to consider new data and, when necessary, revise hazard maps and ensure that the public is fully educated about these changes and communities are appropriately resourced to conduct drills to actually practice their plans.

Japan has invested in technologies like offshore GPS and Canada has invested in ocean bottom seismometers. The United States has not. The U.S. can’t afford not to deploy similar technologies to further improve our understanding of threatening subduction zones. The advancements in earthquake early warning technologies in California and the West Coast of the United States need to be integrated into existing systems and processes so there is no confusion about what life-safety actions need to be taken with perhaps nothing more than a few seconds notice– especially for people living on the coast.

From my perspective, we must always remember that there is a delicate balance between science, technology, and their actual application. Investment in all of the technological marvels one can consider won’t stop the earth from shaking. We must, however, continue to ensure residents and visitors in tsunami hazard zones understand nature’s warning systems and can react quickly and respond appropriately when the time comes.

On March 27, 2014, Senator Mark Begich from Alaska, along with co-sponsors that included Washington State Senator Maria Cantwell and Hawaii Senator Brian Schatz, introduced the Tsunami Warning and Education Reauthorization Act (TWERA). Hopefully, the U.S. House of Representatives will consider this or a similar measure in order to ensure that communities have the resources they need to keep calm, carry on and prepare.

John Schelling is the Earthquake, Tsunami, and Volcano Programs Manager for Washington State Emergency Management (WA EMD) and has extensive experience in emergency management, land use planning, and risk reduction policy analysis. He is currently serving as the Interim Mitigation & Recovery Section Manager for WA EMD.