July 20, 2018

Science & Agriculture: Engagement is a Two-Way Street

Posted by Timia Crisp

Authorship of this guest blog is credited to Rafael Loureiro, PhD. Loureiro is a Research Scientist with Blue Marble Space Institute of Science and an Assistant Professor at Winston-Salem State University.

The ability to ask questions and, more importantly, search for its answers defines our very human nature and shapes our scientific views of the universe and of our place in it. Evidence and open dialog are quintessential parts of this continuous search for the truth which has given us many technological wonders, allowing humankind to achieve the unachievable. From taming nature through agriculture to reaching the furthest places in the cosmos, science is something that defines us as a race; however, most of the general populace tends to enjoy the comforts and conveniences that those discoveries have brought us but may not treasure the process behind it. Overlooking science as a process severely harms a non-scientist’s view on what science is and how the scientific process works. Once established, this view favors only the final result, taking away evidence and dialog from the equation, which dismantles the very pillars of science itself.

The process and the dialog pillars of science were pivotal to steer my interests to make something that was geared to solve one problem, towards solving many others. The OMNICROP initiative was born from a purely space-oriented research that had the sole objective to automate cultivation chambers used by NASA’s Vegetable Production System (Veggie) to grow food for deep-space travels and planetary colonization. Two years were spent gathering data from several sources (e.g. NOAA; USDA) on soil analysis, hemispherical irradiance levels and climatic data along with hundreds of crop yield results from species cultivated worldwide that would allow us to build a model that was able to make those chambers fully automated from seedling to harvesting. The scientific process behind all this data gathering adventure showed us how important agencies like NOAA are for a multitude of applications and that without it we could have never achieved what we have today nor what were trying to achieve back then.

During our presentations, especially the ones given to non-scientists, the question: ‘Why are you worried about feeding astronauts and not the hungry people of the world?” was a constant and even presenting evidence of what we were doing and how it was relevant to humanity’s future could not break one of the most difficult barriers to break between scientists and non-scientists – an open dialog. When there is evidence, but the evidence is blocked by a reluctance to listen and learn from both sides, science is lost. Recognizing that by simply trying to convince the public and policymakers with scientific evidence was not the answer and we started to realize all involved parties (the policymakers, the public and the scientists) must, first, speak the same language and, second, see the importance of the science that is being developed. But how could we relay to them that Earth and space science mattered in their daily lives? How could we create a by-product from something that was strictly space-oriented? How could we follow NASA’s tradition to generate useful, every day applicable tools that came from space research? We listened.

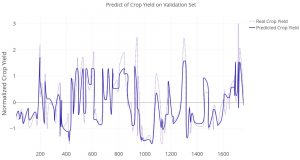

The ever-present question about the world’s food security problems was the answer to our problems. The bridge that we needed between us and them. We had all the tools established and we just needed to shift its gears and take the model out from the lab unto the field. OMNICROP is a model that is able to precisely (to the date of this publication the accuracy stands at 80%) pin-point the ideal crop for any location in the world, predicting that crop’s yield and suggesting other crops for rotation cycles thus lowering the costs of production and pre-planting for small farmers around the globe.

OMNICROP’s example is used to showcase how listening from both ends of the spectrum is utterly important for the success of any scientific project. To acknowledge the fact that your research can have multiple applications beyond its original scope and that something that was initially geared towards deep space exploration can be one of the solutions for worldwide food security, giving importance to not only the end product, but all the processes and agencies behind it. We often blame “them” for not listening, but are we truly open to listen to them ourselves?