August 5, 2014

How Nuclear Waste Disposal Can Help Us Understand Debate Over Fracking

Posted by Fushcia Hoover

By Mohi Kumar

Remember when shale gas was the answer to our energy woes? It was touted as a cheap and plentiful energy source that would reduce our dependence on foreign oil. Industry experts promised jobs, depressed local economies looked to get boosts; with so much good to be had, extracting natural gas from shale looked to be a no-brainer.

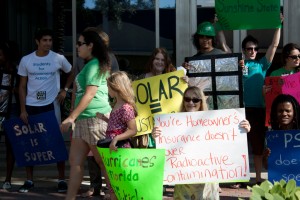

But after fracking began to be an established practice, debate erupted. Anecdotes of flames from kitchen faucets, documentaries such as Gasland spelling out systematic groundwater contamination, explosions of well houses, and seismic activity in places that should be relatively earthquake free began to paint a dark picture of shale gas development. So much so, in fact, that communities are moving to ban fracking from within town limits and numerous grass roots efforts have sprung up to demand that Congress remove hydraulic fracturing exemptions from the the Safe Drinking Water Act.

If the current story-arc of fracking sounds familiar, your sense of déjà vu is spot on. As Wiliam Alley of the National Groundwater Association and coauthors from the University of Guelph and the University of Calgary point out in a recent Eos article, issues surrounding nuclear waste disposal followed the same script.

“After more than half a century, the nuclear industry still has no place for final disposition of its most dangerous wastes. Likewise, the shale gas industry may find itself facing decades of vociferous public opposition,” they write. “It is perhaps ironic that nuclear energy, a mature technology with low greenhouse gas emissions, is now being replaced by lower-cost shale gas, for which the environmental impacts are hotly debated.”

The article, “Nuclear Waste Disposal: A Cautionary Tale for Shale Gas Development” points out the similarities between the factors driving controversies over the two issues.

First, there’s the fear factor—“many perceive the risks of nuclear power and its wastes as uncontrollable, catastrophic, and dreaded,” the authors write. For fracking, “in place of radiation is the fear of unknown chemicals used.” They point out that once fear takes root in people’s minds, it’s hard to shake. This fear is compounded by a lack of trust in the government and “a perceived imbalance of power between ordinary people on one side and ‘big money’ or ‘big oil’ on the other.” Hush-hush attitudes don’t help either:

The nuclear energy industry inherited a culture of isolation and secrecy from the nuclear weapons program. Key decisions on nuclear waste were made with almost no public involvement, and nuclear weapons sites were exempt from pollution control laws for many years.

Shale gas development has its own secrets in the lack of disclosure of fracturing chemicals, leasing activities, and settlement claims. Likewise, the industry has exemptions from various environmental laws and regulations.

In contrast to the public’s fear and lack of trust is “a steady confidence by industry and dismissal of public concerns as irrational,” the authors write. They point to how for a long time, the industry and government thought that nuclear waste disposal was a “trivial technical problem.”

This fostered overconfidence that persisted until research suggested that local hydrological networks could infiltrate nuclear waste disposal sites on faster scales than previously thought. The finding prompted an “abrupt about-face from touting the natural system to an emphasis on…engineered barriers.” This quick shift in focus damaged the public perception of the government’s credibility.

Similarly, technical overconfidence negatively affects public attitudes on the development of shale gas. “Most notable is the statement made by many in the industry that there are no documented cases of hydraulic fracturing contaminating groundwater,” the authors write. It’s a nuanced statement—there are no documented cases because the science isn’t definitively in yet.

But it will be in at some point. Projects are starting to document what’s in the water after fracking at depth. Research has shown that fracking in the Marcellus Shale is freeing radium from shale rocks—this radioactive element seeps into fracking water and finds its way into the water table.

Further, studies have shown that wastewater reinjection of fracking fluids causes earthquakes. In fact, reinjection of fluids used for oil and gas extraction has made Oklahoma the home to more small earthquakes (of a magnitude 3 or less) than California. Though the latter study does not specifically implicate wastewater reinjection from fracking, it does suggest that seismic spikes may be likely wherever reinjection of fracking water occurs.

“Given the uncertainties and economic importance of shale gas development, a comprehensive scientific effort is needed to evaluate the environmental impacts and inform the regulatory framework,” the authors write.

Also needed is more communication between industry and the public, according to U.S. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell. In her keynote at this year’s AGU science policy conference, Jewell stated that hydraulic fracturing is an “example of the public not being brought along to understand the risk [of fracking], and industry not doing the job that it could have done up-front in helping people understand the risks and benefits and reassuring people that their groundwater was not going to be contaminated.” Sounds familiar?

Progress, then, could be potentially found through sound science and good communication. And we can learn valuable lessons in both from history

Mohi Kumar is a writer and editor in AGU’s Marketing, Communications and Engagement Department.

Good points and seems very well balanced.

It seems to me that this article underplays how much is actually known about hydraulic fracturing and its likely impacts. Very little note has been taken of the fact that the chemicals used in fracturing still have to be documented to some degree by MSDS sheets, which were invented so that one did not have to be a PhD to react to releases. So the main impacts and remedial actions are documented. The only reason to need full chemical formulas for these chemicals as far as I can tell is forensic – so that lawyers can find someone to blame for any releases. These matters deserve serious discussion, but I feel this article is weak on what is already known.

Although I have not read the cited article, as the former branch chief for performance assessment at Yucca Mountain, I feel the description of the balance between engineered and natural barriers for the deep geologic disposal system is oversimplified. I also certainly never saw anyone working on performance assessment dismiss as trivial the questions we were answering. The parallel is mostly relevant, however. The National Academy of Sciences had weighed in on appropriate solutions, but to my knowledge never dismissed the issue of disposal as trivial.